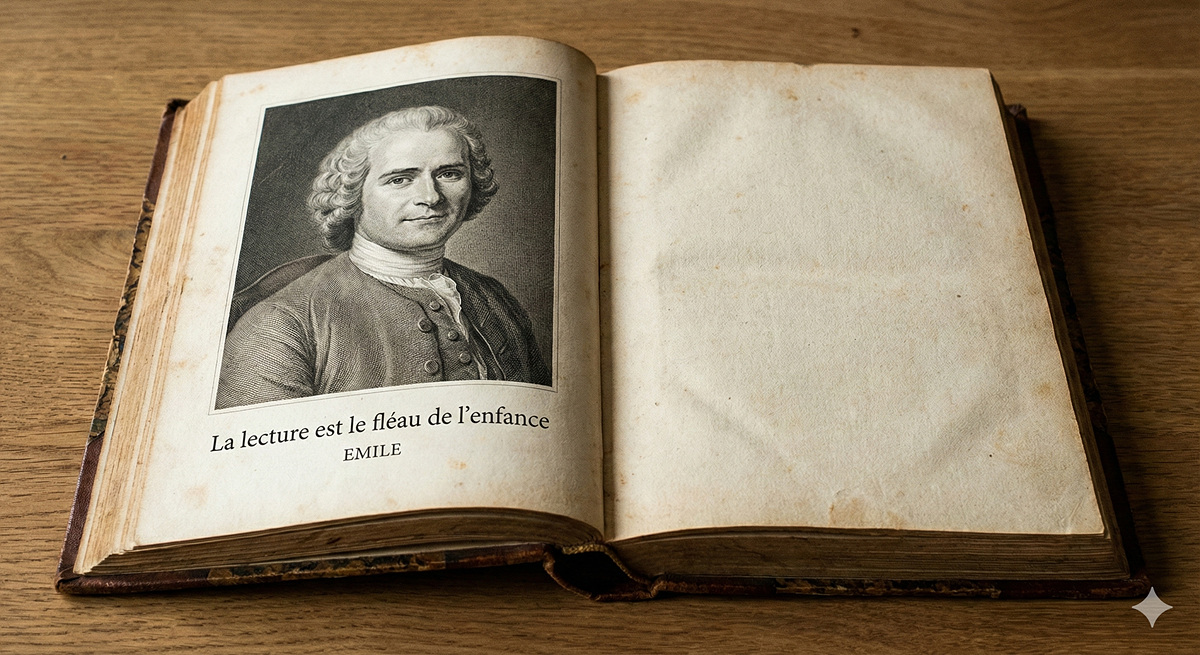

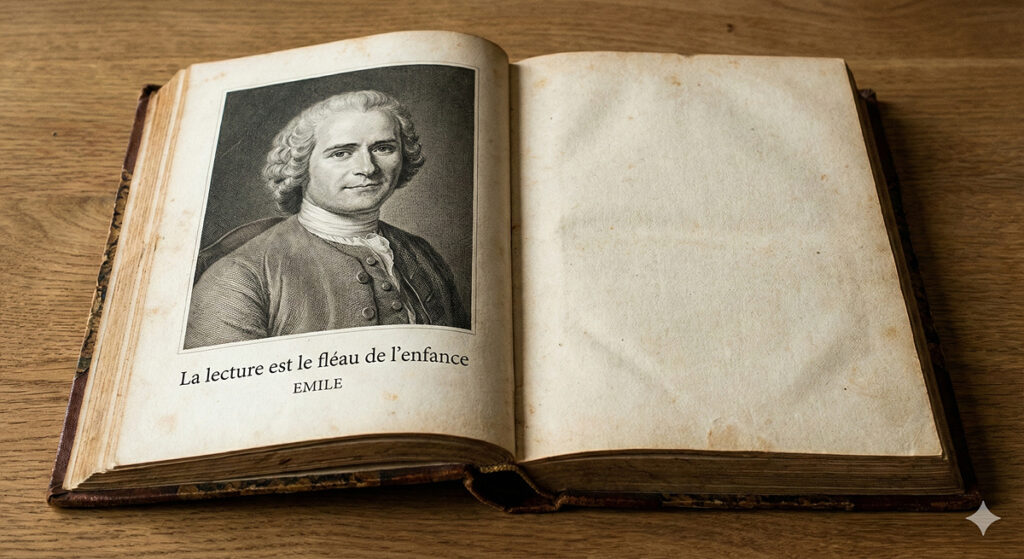

“독서는 아이들에게 재앙이다.”

장 자크 루소는 그의 저서 《에밀》에서 이렇게 말했다. 책 육아가 정답이 된 ‘요즘 한국 부모들’이 이 말을 들으면 기절초풍하겠지만, 21세기 대한민국에서 이 문장은 신성모독이나 다름없다. 한국 부모들에게 독서는 단순한 읽기가 아니다. 그것은 문해력을 기르고 명문 대학을 가기 위한 신성한 의식이다.

하지만 이 신성함 뒤에는 촌극이 숨어 있다. 통계에 따르면 한국 40대의 독서율은 OECD 국가 중 최하위 수준이다. 정작 자신들은 일 년에 책 한 권 제대로 읽지 않으면서, 아이들의 손에 들린 스마트폰과 텔레비전은 영혼을 파괴하는 악마로 정죄한다.

물론 나 역시 영유아 시기의 아이들에게는 디지털 미디어 노출이, 심지어는 과도한 책 육아조차도 위험할 수 있다는 점에는 동의한다. 루소가 경계했듯, 세상을 갓 배우는 그 시기에는 매체 속에 갇히기보다 오감으로 직접 세상을 느끼는 것이 훨씬 중요하기 때문이다.

하지만 아이가 자라고 세상을 넓혀가야 할 시점, 나이가 되었는데도, 여전히 이분법적 잣대만 들이대는 것은 문제다.

역사적으로 새로운 미디어 플랫폼은 언제나 ‘두들겨 맞는’ 동네북이었다. 소크라테스는 글자가 사람들의 기억력을 감퇴시킬 것이라며 반대했고, 18세기엔 소설이 부녀자를 타락시킨다고 비난받았다. 지금 우리가 스마트폰을 보며 혀를 차듯, 과거엔 책조차도 ‘현실을 가리는 위험한 매체’였다. 결국 책도 미디어일 뿐이다.

그런데 유독 한국 사회는 책을 ‘절대 선(善)’의 위치에 올려두고, 그 안에서도 철저하게 계급을 나눈다. 학습만화는 나쁜 것, 만화책은 저급한 것, 오직 순수 문학이나 권위 있는 상을 받은 책만이 읽어야 할 ‘진짜 책’으로 대접받는다. 부모는 검열관이 되어 엄선된 고상한 책만을 아이의 식탁에 강제로 밀어 넣는다.

그래서, 그 아이들이 책을 사랑하게 되었는가? 부모의 통제가 사라진 중학생이 되어서도, 어른이 되어서도 스스로 책을 펼치는가? 억지로 떠먹여진 밥이 체하듯, 강요된 독서는 책에 대한 혐오만 남길 뿐이다.

나 또한 책을 좋아한다. 특히 로맨스 스릴러 장르는 손에서 놓지 못할 만큼 애정한다. 내가 책을 읽는 이유는 그것이 ‘고상한 행위’여서가 아니다. 단지 읽으면 즐겁기 때문이다. 나는 넷플릭스나 유튜브를 즐겨 보지는 않는 편이지만, 책만이 우상시되고 다른 미디어는 악마화되는 이 현상이 기이하게 느껴질 뿐이다.

우리는 거실에서 어떤 풍경을 만드는가. 부모의 손에는 24시간 스마트폰이 들려 있다. 아이가 다가와 말을 걸면 건성으로 대답하며 시선은 액정에 고정한다. 죄책감을 덜기 위해 그들은 스스로에게 최면을 건다. “이건 노는 게 아니야, 업무를 보는 거야.” 아이의 눈에 비친 부모는 그저 ‘나보다 핸드폰을 더 좋아하는 사람’일 뿐인데도 말이다.

그러면서 아이를 향해서는 통제의 칼을 휘두른다. “너는 폰 그만 보고 책 읽어.” 부모가 책을 읽지 않는 집에서, 아이에게 독서는 즐거운 탐험이 아니라 부모가 자신을 묶어두기 위한 ‘통제 수단’으로 전락한다.

초등학교 입학은 이 단절의 가속화 구간이다. “이제 초등학생이니 놀지 마라”는 명령과 함께 아이들은 학원 뺑뺑이의 굴레로 들어간다. 친구들과 마라탕을 먹고 네컷 사진을 찍으며 웃는 시간은 ‘쓸데없는 시간 낭비’이자 ‘돈 낭비’로 취급된다.

대신 그 자리를 채우는 건 주말의 박물관과 도서관 나들이다. 그들은 아이 손을 잡고 도서관을 찾는 자신들의 ‘고상한 육아’에 도취되어, 아이에게 게임을 허용하고 친구들과 놀게 해주는 부모들에게 무언의 돌을 던진다. 자신들은 정작 책 한 줄 읽지 않으면서 느끼는 그 우월감, 그것은 교양이라는 가면을 쓴 명백한 위선이다.

진짜 위험한 것은 마라탕도, 아이들의 유튜브나 로블록스도 아니다.(물론 하루종일 핸드폰을 놓지 않는 아이들은 절제와 통제력을 가르쳐주는것이 맞다)

소통은 거세된 채, 일방적인 통제와 맹목적인 학습만이 남은 차가운 거실이다.

책을 읽으라고 소리치기 전에, 스마트폰을 내려놓고 아이의 눈을 한 번 더 바라봐야 한다. 아이가 학교에서 무슨 일이 있었는지 신나게 ‘썰’을 풀 때, 그 이야기에 귀 기울여주는 것이 먼저다. 아이들에게 필요한 건 대학을 가기 위한 도구로서의 책이 아니라, 순수하게 이야기가 주는 즐거움이다.

하지만 요즘 맘카페에서는 “순수 독서만으로는 문해력과 논술 실력을 채울 수 없으니 결국 논술 학원에 보내야 한다”는 말이 정설처럼 돈다. 책을 읽는 가장 원초적인 즐거움조차 ‘성적에 도움이 되느냐’로 난도질당하는 현실이 너무나 슬프다.

우리는 인정해야 한다. 우리 아이들은 태어날 때부터 디지털 기기와 함께 숨 쉬어 온 ‘디지털 네이티브’다. 무작정 금지하고 오로지 책만 강요하는 육아보다는, 활자든 디지털이든 그 경험을 함께 공유하는 지혜가 필요하다. 아이들 세대의 또래 문화에 관심을 보여주고, 단순히 디지털 미디어를 소비하는 것에 그치지 않고 함께 생산적인 활동으로 나아가는 것이다.

책을 읽는 것에서 멈추지 않고 아이와 머리를 맞대고 웹소설을 써본다거나, 유튜브 숏폼을 멍하니 바라보는 대신 함께 여행 브이로그를 찍어보거나 함께 챌린지 춤을 추는건 어떨까? 일방적인 시청이나 강요된 독서보다, 무언가를 함께 만들어가는 과정에서 피어나는 가족 간의 소통이 훨씬 더 건설적일 것이다.

오늘날 한국 사회는 ‘혐오’가 기본값이 되어버렸다. 내 방식만 옳고 타인의 사는 방식은 너무나 쉽게 힐난한다. 나 또한 잘난 하며 글을 썼지만, 나 역시 그 혐오의 시선에서 자유롭지 못했음을 고백한다. 우리에게 필요한 건 서로의 다름을 인정하는 관용적 시선, 그리고 타인의 삶에 대한 최소한의 매너가 아닐까.

The Idol of Books and the Hypocrisy of Smartphone-Wielding Parents

“Reading is the scourge of childhood.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote this in his book Emile. While an 18th-century philosopher might say this, in 21st-century Korea, this sentence is nothing short of blasphemy. Here, “Book Parenting” is a religion. For Korean parents, reading is not just reading; it is a sacred ritual for literacy and university admission.

However, behind this sanctity lies a farce. Statistics show that the reading rate of Koreans in their 40s is among the lowest in the OECD. Parents themselves barely read one book a year, yet they condemn the smartphones and TVs in their children’s hands as demons destroying their souls.

Of course, I agree that exposure to digital media—and even excessive forced reading—can be dangerous for toddlers. As Rousseau warned, at that young age, it is far more important to experience the world with one’s five senses than to be trapped in any medium.

But the problem is applying this binary standard even as children grow and their worlds expand.

Historically, new media platforms have always been the punching bag. Socrates opposed writing, claiming it would destroy memory, and in the 18th century, novels were blamed for corrupting women. Just as we click our tongues at smartphones today, books were once considered a “dangerous medium that obscures reality.” Ultimately, a book is just another form of media.

Yet, Korean society places books on an absolute pedestal of “Good.” Even within books, there is a rigid class system. Educational comics are “bad,” and comic books are “low-class.” Only pure literature or award-winning authoritative books are treated as “real books.” Parents become censors, forcing only these selected, “noble” books onto their children’s plates.

So, did those children grow up to love books? Do they open books on their own when they become middle schoolers or adults, free from parental control? Just as forced feeding causes indigestion, forced reading only leaves a hatred for books.

I also love books. I especially adore romance thrillers. But I don’t read them because it’s a “noble act.” I read them simply because they are fun. I don’t enjoy Netflix or YouTube much, but I find it bizarre that books are idolized while other media are demonized.

Let’s look at our living rooms. Parents hold smartphones 24/7. When a child speaks, they answer half-heartedly, eyes glued to the screen. To alleviate guilt, they hypnotize themselves: “I’m not playing; I’m working.” But in the child’s eyes, the parent is just “someone who likes their phone more than me.”

While doing so, they wield the sword of control over their children: “Stop looking at your phone and go read a book.” In a house where parents don’t read, reading becomes a tool of control, not an enjoyable exploration.

Elementary school entry accelerates this disconnection. With the command, “You’re a student now, stop playing,” children enter the loop of cram schools (Hagwons). Time spent eating Mara-tang (spicy hot pot) with friends or taking “four-cut photos” in booths is treated as a waste of time and money.

Instead, weekends are filled with visits to museums and libraries. Parents get drunk on their own “noble parenting,” silently judging other parents who let their kids play games. The sense of superiority they feel, while not reading a single line themselves, is hypocrisy masked as culture.

The real danger is not the Mara-tang, nor children’s YouTube or Roblox. (Of course, children who are glued to their phones all day do need to be taught moderation and self-control.) It is the cold living room where communication is castrated, leaving only one-way control and blind learning.

Before shouting at them to read, parents should put down their smartphones and look into their children’s eyes. We need to listen when they excitedly tell their stories. What children need is not books as a tool for college, but the pure joy of stories.

However, it is truly heartbreaking to hear people in online parenting communities (‘Mom Cafes’) say, “Pure reading isn’t enough for literacy and essay scores, so you must send them to an essay academy.” It is tragic that even the simple joy of reading is being disregarded if it doesn’t guarantee high grades.

We must admit it. Our children are “digital natives” who have breathed with digital devices since birth. Instead of blindly banning them and forcing only books, we need the wisdom to share experiences—whether through print or digital media. We should take an interest in peer culture and move beyond consumption to productive activities together.

Why not write a web novel together instead of just reading? Why not film a travel vlog together instead of blankly staring at YouTube Shorts? Communication that blooms from creating something together is far more constructive than one-sided viewing or forced reading.

In today’s society, hatred has become the default. We believe only our way is right and easily criticize how others live. I, too, wrote this with a critical pen, but I confess I am not free from that gaze of hatred. Perhaps what we truly need is a tolerant view of our differences and minimum manners toward the lives of others.